Controlling reactions

C5: Monitoring and controlling chemical reactions

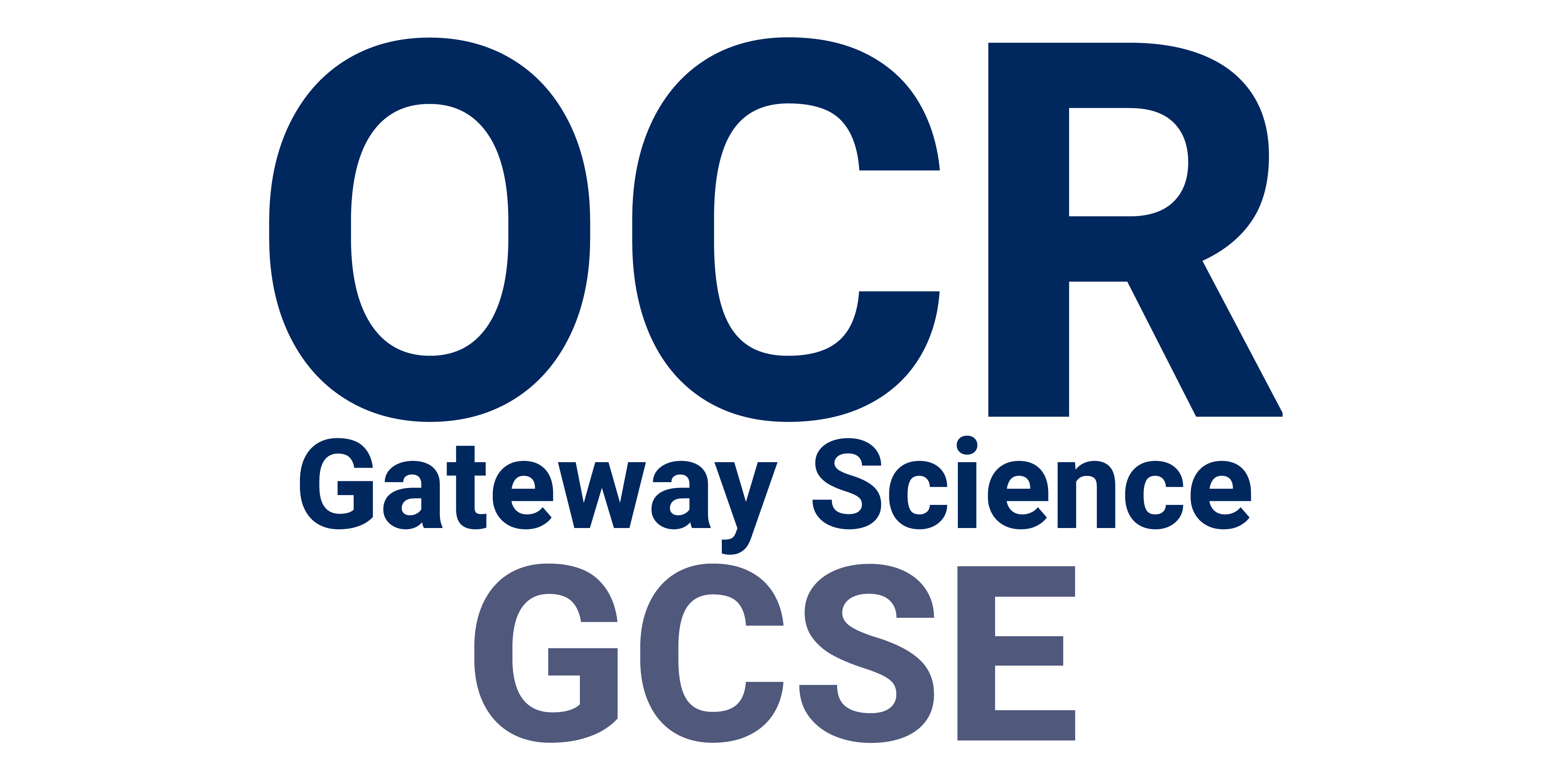

Collision Theory

Chemical reactions take place when the reactant particles collide together, and then form new products.

Not every collision is successful. The particles have to collide:

- with the right orientation (facing the correct way)

- with the right amount of energy (the activation energy)

Rates of reaction are increased when the frequency and/or the energy of collisions is increased.

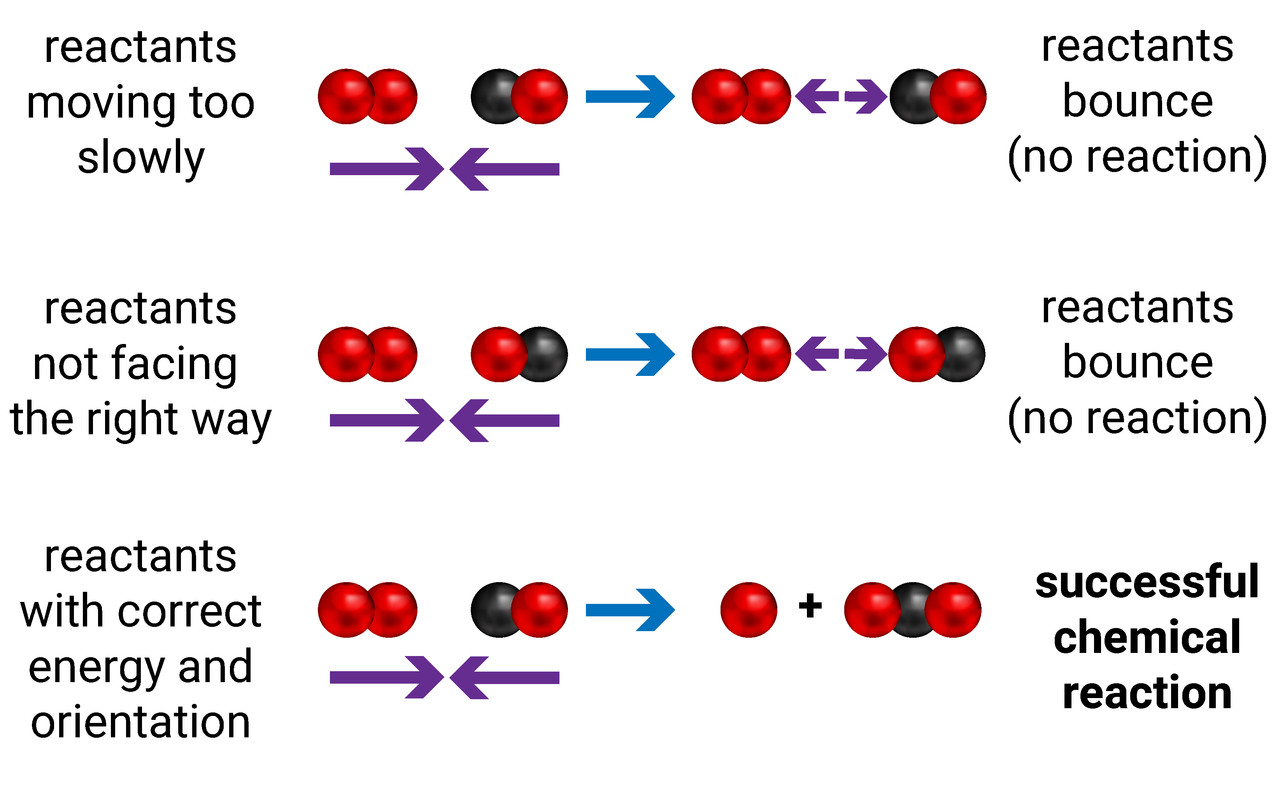

Factors Affecting Rates

Temperature

Increasing the temperature of a reaction gives the particles more energy to collide. This leads to more frequent, successful collisions and so the rate of reaction increases.

Concentration of solution, or Pressure of gas

Increasing the concentration/pressure of reactants increases the amount of particles in a given volume. This leads to more frequent, successful collisions and so the rate of reaction increases.

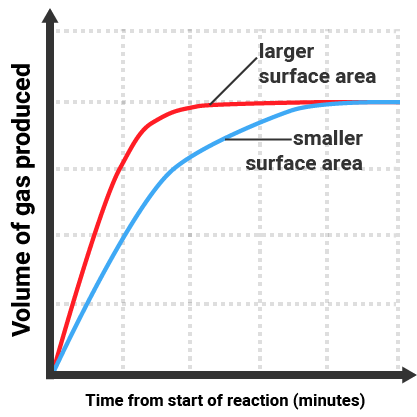

Surface area of solid reactants

Increasing the surface area of reactants frees up more particles that are available to collide right away. This doesn't add more particles in to the reaction, it only makes available particles that would have once waited for other particles to react first until they could be available. This leads to more frequent, successful collisions and so the rate of reaction increases.

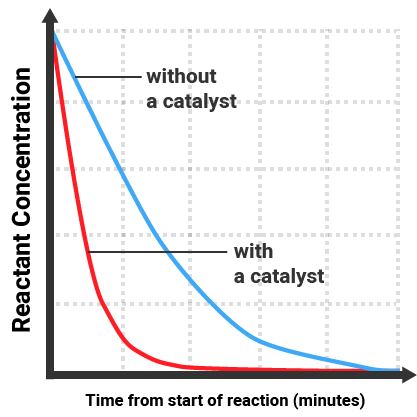

Catalysts

Catalysts are substances that speed up the rate of a reaction without altering the products of the reaction, being itself unchanged chemically (and in mass) at the end of the reaction.

They provide an an alternative pathway for a reaction, reducing the activation energy of the reaction; causing more frequent, successful collisions and so the rate of reaction increases.

Enzymes are biological catalysts and are used in the production of alcoholic drinks (among other things).

Measuring Rates

There are three main ways to measure the rate of a reaction:

- the change of mass of reactants over time

- the volume of gas produced over time

- the time taken for a solution to change colour, or form a precipitate

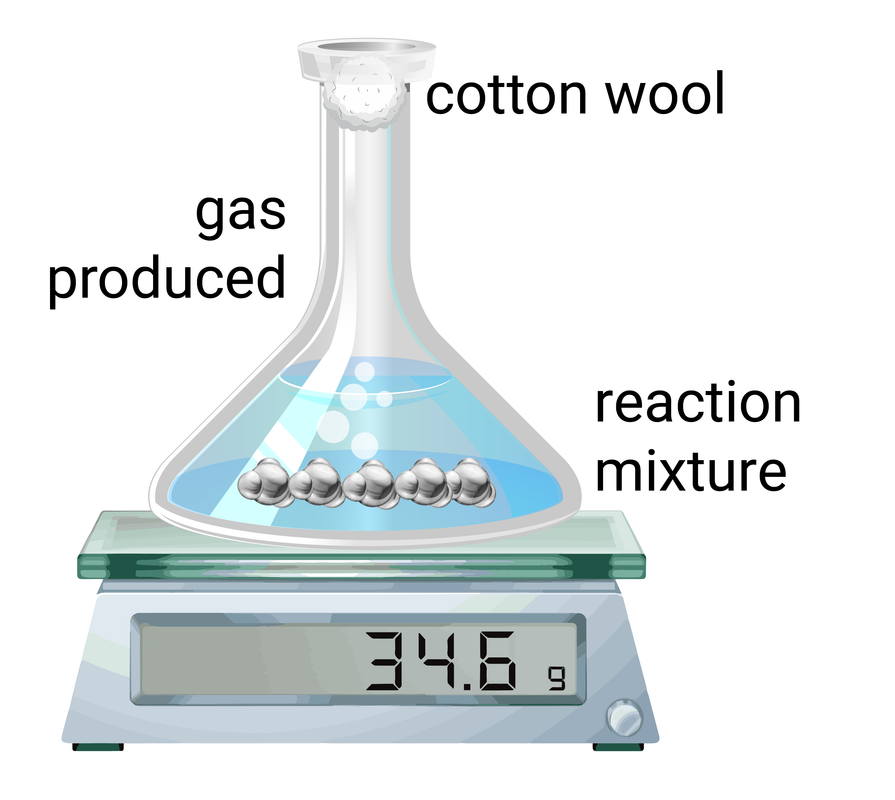

Mass change

This method works by measuring the amount of mass change during set time intervals, and then the data can be plotted on a graph.

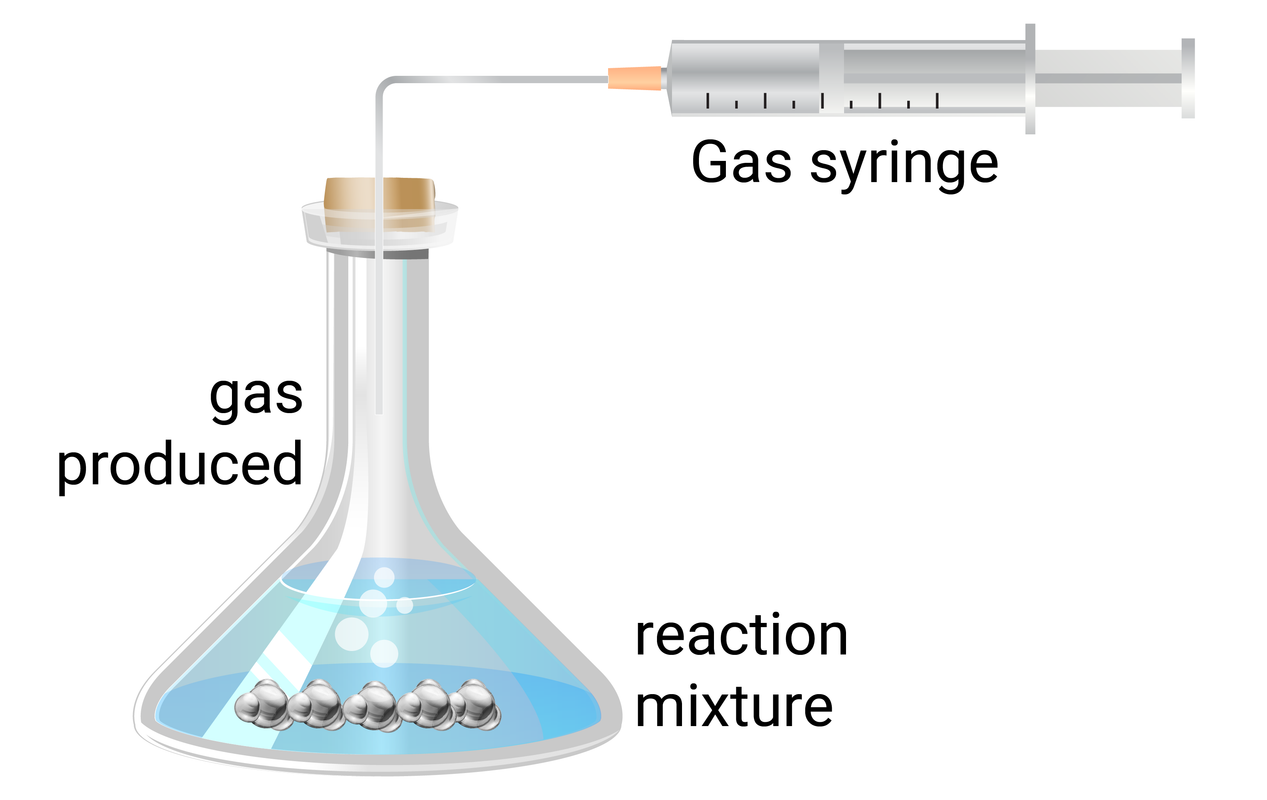

Volume of gas

This method is often easier than measuring small changes in mass. This method works by measuring the amount of gas collected during set time intervals, and then the data can be plotted on a graph.

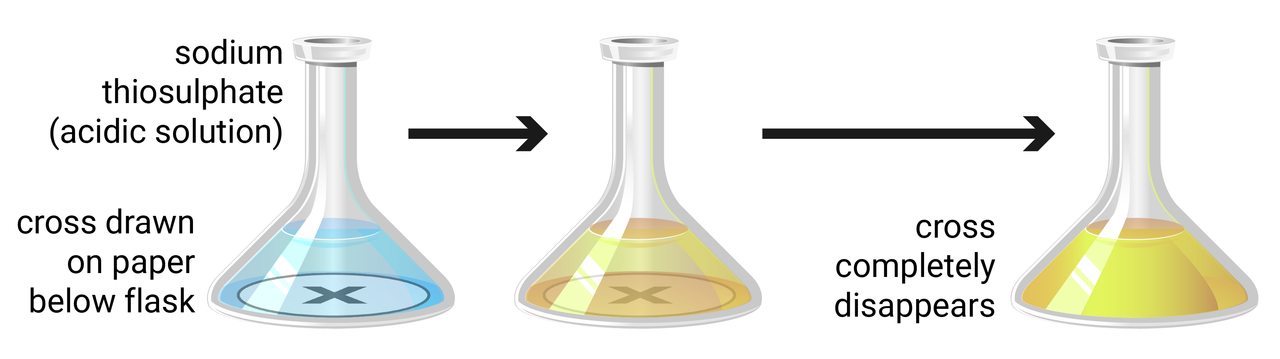

Colour change/precipitation

This can either be done to measure the change in colour, or to measure change in opaqueness (disappearing cross - as the cross slowly 'disappears' due to precipitate forming). The end point is quite inaccurate when using the human eye, so to increase accuracy we can use digital data loggers instead.

Calculating Rate

The shorter the reaction time is, the faster the rate of the reaction. We can calculate rate of reaction using one of three equations:

rate = quantity of reactant used ÷ time taken

or

rate = quantity of product made ÷ time taken

or

rate = change in mass ÷ change in time

or

rate = change in volume ÷ change in time

The gradient of the line is equal to the rate of reaction. The reaction with the higher temperature:

- gives a steeper line (gradient)

- finishes sooner

- still produces the same mass increase

The gradient of the line is equal to the rate of reaction. The reaction with the larger surface area:

- gives a steeper line (gradient)

- finishes sooner

- still produces the same volume increase

The gradient of the line is equal to the rate of reaction. The reaction with a catalyst:

- gives a steeper line (gradient)

- finishes sooner

- still causes all reactant to be used up